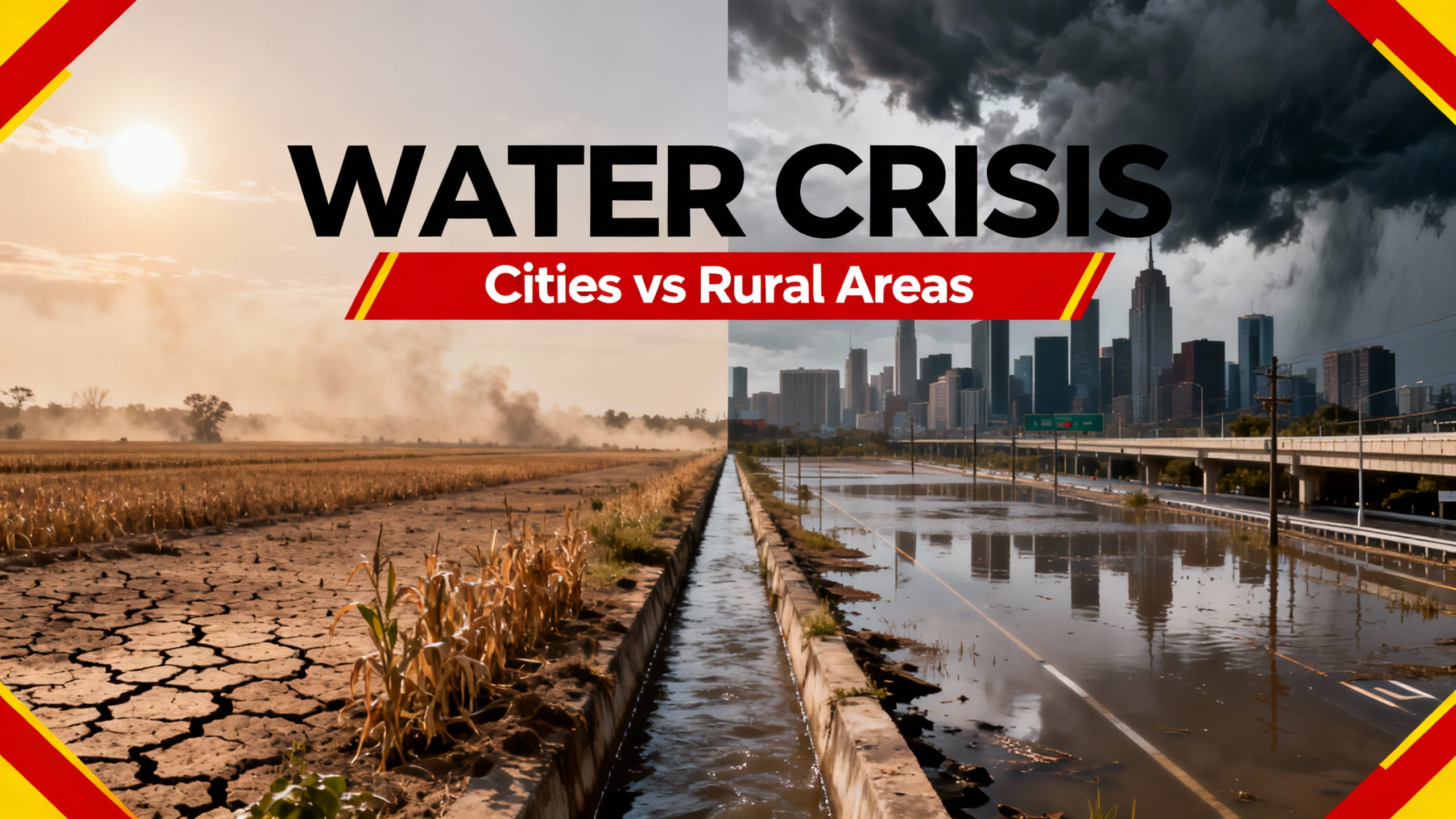

Water used to be the one thing planners could count on. Rain fell where it usually did. Rivers rose and receded on familiar schedules. Groundwater tables moved slowly enough that nobody worried much about tomorrow. That certainty is gone. From drought-hit farming belts to flood-prone megacities, climate change is quietly—and sometimes violently—rewriting the rules of water availability.

The story isn’t just about “less water” or “more floods.” It’s about timing, location, quality, and who gets access when systems are under stress. And the divide between rural and urban regions is becoming sharper by the year.

A Climate-Driven Water Reset

Climate change affects water through a few blunt mechanisms: higher temperatures increase evaporation, warmer air holds more moisture, and weather systems behave less predictably. According to the U.S. Global Change Research Program, heavy rainfall events in the U.S. have increased by more than 40% in some regions since the mid-20th century, even as droughts have intensified elsewhere.

Globally, the World Meteorological Organization notes that water-related disasters now account for nearly 90% of climate-related natural disasters, a figure detailed in its annual climate assessments published at https://wmo.int.

The result is a hydrological whiplash—too much water arriving too fast, followed by long dry spells that drain rivers, reservoirs, and aquifers.

Rural Regions: When Rain No Longer Follows the Crops

In rural areas, especially those dependent on agriculture, climate-driven water shifts hit first and hardest. Farming still relies heavily on predictable rainfall patterns, even in places with irrigation infrastructure.

Hotter temperatures accelerate soil moisture loss, meaning crops need more water even as rainfall becomes less reliable. In parts of the U.S. Midwest, spring rains are intensifying while summers grow drier—bad news for corn and soybean yields that depend on mid-season moisture. The U.S. Department of Agriculture has repeatedly flagged climate-related water stress in its outlooks, available via https://www.usda.gov.

Groundwater, once considered a dependable backup, is also under pressure.

Groundwater Stress in Agricultural Zones

Across India, the U.S., China, and parts of the Middle East, farmers are pumping aquifers faster than nature can refill them. Climate change worsens the imbalance by reducing snowpack and altering recharge rates.

The U.S. Geological Survey reports declining groundwater levels across major agricultural basins, including the High Plains Aquifer, with long-term monitoring data published at https://www.usgs.gov.

When wells run dry, rural communities face a stark choice: abandon land, switch crops, or invest in expensive water-saving technologies many can’t afford.

Urban Areas: Floods, Shortages, and Aging Systems

Cities, paradoxically, are dealing with both scarcity and excess. Climate change exposes weaknesses in urban water systems that were designed for a different era.

Many major cities rely on distant water sources—mountain snowpack, large reservoirs, or river systems shared with agriculture. As snow melts earlier and droughts linger longer, those supplies become less reliable. Cape Town’s near “Day Zero” crisis in 2018 wasn’t a fluke; it was a preview.

Meanwhile, heavier rainfall overwhelms stormwater systems, leading to flash floods and sewage overflows. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency has repeatedly warned that combined sewer systems in older cities are ill-equipped for modern rainfall extremes, a concern outlined in regulatory guidance at https://www.epa.gov.

The Urban Heat and Water Trap

Cities also amplify climate impacts through heat islands. Hotter urban temperatures increase water demand just as supplies become strained. Leaks in aging infrastructure—some U.S. cities lose 20–30% of treated water before it reaches taps—turn scarcity into crisis.

| Urban Water Challenge | Climate Driver | Consequence |

|---|---|---|

| Flooding | Intense rainfall | Infrastructure damage, contamination |

| Water shortages | Drought, heat | Rationing, price hikes |

| Quality degradation | Warmer water | Algal blooms, treatment costs |

Water Quality: The Hidden Crisis

Availability isn’t just about quantity. Climate change is degrading water quality in ways that affect both rural and urban users.

Warmer waters encourage harmful algal blooms in lakes and reservoirs, contaminating drinking supplies. Agricultural runoff becomes more concentrated during heavy rains, pushing nitrates and pesticides into rivers. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has linked climate-driven water quality changes to rising public health risks, detailed at https://www.cdc.gov.

In rural areas, private wells often lack treatment systems, making communities vulnerable to contamination after floods or prolonged droughts. Urban utilities face skyrocketing treatment costs, expenses that ultimately land on ratepayers.

The Rural–Urban Water Divide Is Widening

Climate change doesn’t hit evenly. Wealthier urban centers often have the political and financial clout to secure water through infrastructure investments, inter-basin transfers, or desalination. Rural regions, especially in developing countries, rarely have that luxury.

This imbalance raises uncomfortable questions about equity. Who gets water during a prolonged drought? Which communities absorb the risk when rivers run low? These tensions are already surfacing in disputes over river basins like the Colorado, the Nile, and the Indus.

Adaptation Strategies Taking Shape

Despite the challenges, adaptation is underway—sometimes quietly, sometimes under pressure.

What’s Working in Rural Areas

- Shifts toward drought-resistant crops

- Precision irrigation and soil moisture monitoring

- Managed aquifer recharge during wet years

Urban Adaptation Playbooks

- Green infrastructure to absorb rainfall

- Water recycling and reuse systems

- Leak detection using AI-driven monitoring

Countries like Singapore have become case studies in urban water resilience, combining aggressive conservation with advanced treatment technology, a model frequently cited by the United Nations at https://www.unwater.org.

Fact Check: Is Climate Change Really Driving Water Scarcity?

Yes. Multiple independent assessments confirm the link between climate change and altered water availability. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) concludes with high confidence that climate change has already intensified the global water cycle, increasing both drought and flood risks. These findings are publicly available through official summaries at https://www.ipcc.ch.

Water stress today is not just a population or management issue—it is a climate issue.

Where This Leaves Us

Water is becoming the frontline of climate change, the place where abstract temperature charts turn into lived experience. For rural regions, it’s about livelihoods and survival. For cities, it’s about resilience and social stability. The old assumption—that water will show up where and when we need it—is no longer safe.

The next decade will likely determine whether adaptation keeps pace with reality or whether water becomes the defining scarcity of a warming world.

FAQs

How does climate change reduce water availability?

It alters rainfall patterns, increases evaporation, reduces snowpack, and intensifies droughts and floods, making water supplies less predictable.

Why are rural areas more vulnerable to water stress?

Rural economies often depend directly on rainfall and groundwater for agriculture, with limited infrastructure to buffer climate shocks.

Are cities running out of water?

Some are facing serious shortages, especially during droughts, while others struggle with flooding due to outdated infrastructure.

How does climate change affect water quality?

Warmer temperatures and intense rainfall increase pollution, algal blooms, and contamination risks.